New Interpretation of Antarctic Ice Cores

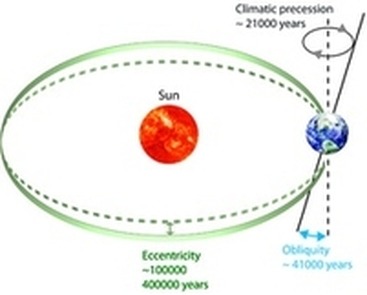

The variations in the Earth’s orbit and the inclination of the Earth have given decisive impetus to the climate changes over the last million years. Serbian mathematician Milutin Milankovitch calculated their influence on the seasonal distribution of insolation back at the beginning of the 20th century and they have been a subject of debate as an astronomic theory of the ice ages since that time. Because land surfaces in particular react sensitively to changes in insolation, whereas the land masses on the Earth are unequally distributed, Milankovitch generally felt insolation changes in the northern hemisphere were of outstanding importance for climate change over long periods of time. His considerations became the prevailing working hypothesis in current climate research as numerous climate reconstructions based on ice cores, marine sediments and other climate archives appear to support it.

AWI scientists Thomas Laepple, Gerrit Lohmann and Martin Werner have analysed again the temperature reconstructions based on ice cores in depth for the now published study. For the first time they took into account that the winter temperature has a greater influence than the summer temperature in the recorded signal in the Antarctic ice cores. If this effect is included in the model calculations, the temperature fluctuations reconstructed from ice cores can also be explained by local climate changes in the southern hemisphere.

Thomas Laepple explains the significance of the new findings: “Our results are also interesting because they may lead us out of a scientific dead end.” After all, the question of whether and how climate activity in the northern hemisphere is linked to that in the southern hemisphere is one of the most exciting scientific issues in connection with our understanding of climate change. Thus far, many researchers have attempted to explain historical Earth climate data from Antarctica on the basis of Milankovitch’s classic hypothesis. “To date, it hasn’t been possible to plausibly substantiate all aspects of this hypothesis, however,” states Laepple. “Now the game is open again and we can try to gain a better understanding of the long-term physical mechanisms that influence the alternation of ice ages and warm periods.”

Thomas Laepple explains the significance of the new findings: “Our results are also interesting because they may lead us out of a scientific dead end.” After all, the question of whether and how climate activity in the northern hemisphere is linked to that in the southern hemisphere is one of the most exciting scientific issues in connection with our understanding of climate change. Thus far, many researchers have attempted to explain historical Earth climate data from Antarctica on the basis of Milankovitch’s classic hypothesis. “To date, it hasn’t been possible to plausibly substantiate all aspects of this hypothesis, however,” states Laepple. “Now the game is open again and we can try to gain a better understanding of the long-term physical mechanisms that influence the alternation of ice ages and warm periods.”

“Moreover, we were able to show that not only data from ice cores, but also data from marine sediments display similar shifts in certain seasons. That’s why there are still plenty of issues to discuss regarding further interpretation of palaeoclimate data,” adds Gerrit Lohmann. The AWI physicists emphasise that a combination of high-quality data and models can provide insights into climate change. “Knowledge about times in the distant past helps us to understand the dynamics of the climate. Only in this way will we learn how the Earth’s climate has changed and how sensitively it reacts to changes.”

The new study does not call into question that the currently observed climate change has, for the most part, anthropogenic causes. Cyclic changes, as those examined in the Nature publication, take place in phases lasting tens of thousand or hundreds of thousands of years. The drastic emission of anthropogenic climate gases within a few hundred years adds to the natural rise in greenhouse gases after the last ice age and is unique for the last million years. How the climate system, including the complex physical and biological feedbacks, will develop in the long run is the subject of current research at the Alfred Wegener Institute.